INTRODUCTION

Legend has it that New Zealand was discovered by Kupe, an early Maori explorer who when seeing some low clouds on a distant horizon announced to his starving crew, “We have found a new land.” They probably said, “Yeah, yeah, whatever,” but as they paddled closer, the snowy peaks of the Southern Alps did indeed loom out of the clouds and Kupe was proven to be right.

He named the new country “Aotearoa” – The Land of the Long White Cloud.

On 29th May 2000, there was an army coup in Fiji in reaction to an Indo-Fijian, Mahendra Chaudhry, being elected as the first non-Fijian Prime Minister.

Fiji’s President Ratu Sir Kamasese Mara, himself a high-born leader of the Council of Chiefs, was not unsympathetic to the coup. Much to his annoyance, a New Zealand warship was dispatched to Suva Bay to keep an eye on things. That was when Ratu Mara retaliated by branding New Zealand, “The Land Of The Wrong White Crowd.” — Clever!

I was born the generation before the baby boomers. In my teenage years, there were plenty of jobs, NZ was rebuilding and with “the second war to end all wars” behind us, optimism prevailed. We lived in an insular society thousands of miles away from most of the civilised world.

Cutting and bagging chaff for winter feed.

The first time I heard a foreign language was when one of Hitler’s broadcasts was relayed by the BBC in the war’s final months. The second was at high school when our new French teacher said “bonjour” to us for the first time in her broad NZ accent.

In those days we were very much an Anglo-Saxon mob on the one hand and an underprivileged Maori minority on the other. It would be a decade or two yet before second and third-generation New Zealanders stopped saying “I’m going home to the old country” when heading off on a once-in-a-lifetime overseas trip to the UK.

I left home permanently when I was 15. At that age, you were old enough to leave school, get your driver’s license and own a rifle. There was a shortage of manpower, and school leavers could walk into almost any job that interested them.

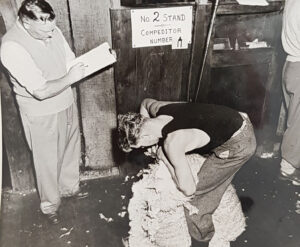

Me at a young farmers’ shearing competition.

I wanted to be a farmer and happily went off to the Wairarapa Training Farm, an institution providing a two-year training course for young boys to become farmers.

Sixteen cadets worked the farm under the watchful eyes of three working instructors and a house master who also had the unpopular task of allotting kitchen and gardening duties.

On Friday afternoons the hawk-eyed housemaster’s wife supervised the scrubbing of our smelly work clothes before we were inspected and then driven into Masterton to go to the pictures.

Our pocket money was five shillings a week in the first year and seven shillings and sixpence in the second year.

Washed and scrubbed and ready for the Friday night pictures in Masterton. We all smelt good on Fridays!

Time spent at the training farm were my growing-up years, and I remember them fondly.

When my two-year training period was over, and after a short holiday back at home in Lower Hutt, I took off once again on the long train ride to Gisborne on the East Coast of the North Island. There I started my first paid job as a shepherd and farm hand on Te Ruanui Station. I wrote about that in a previous blog, “A Tribute to Working Dogs.”

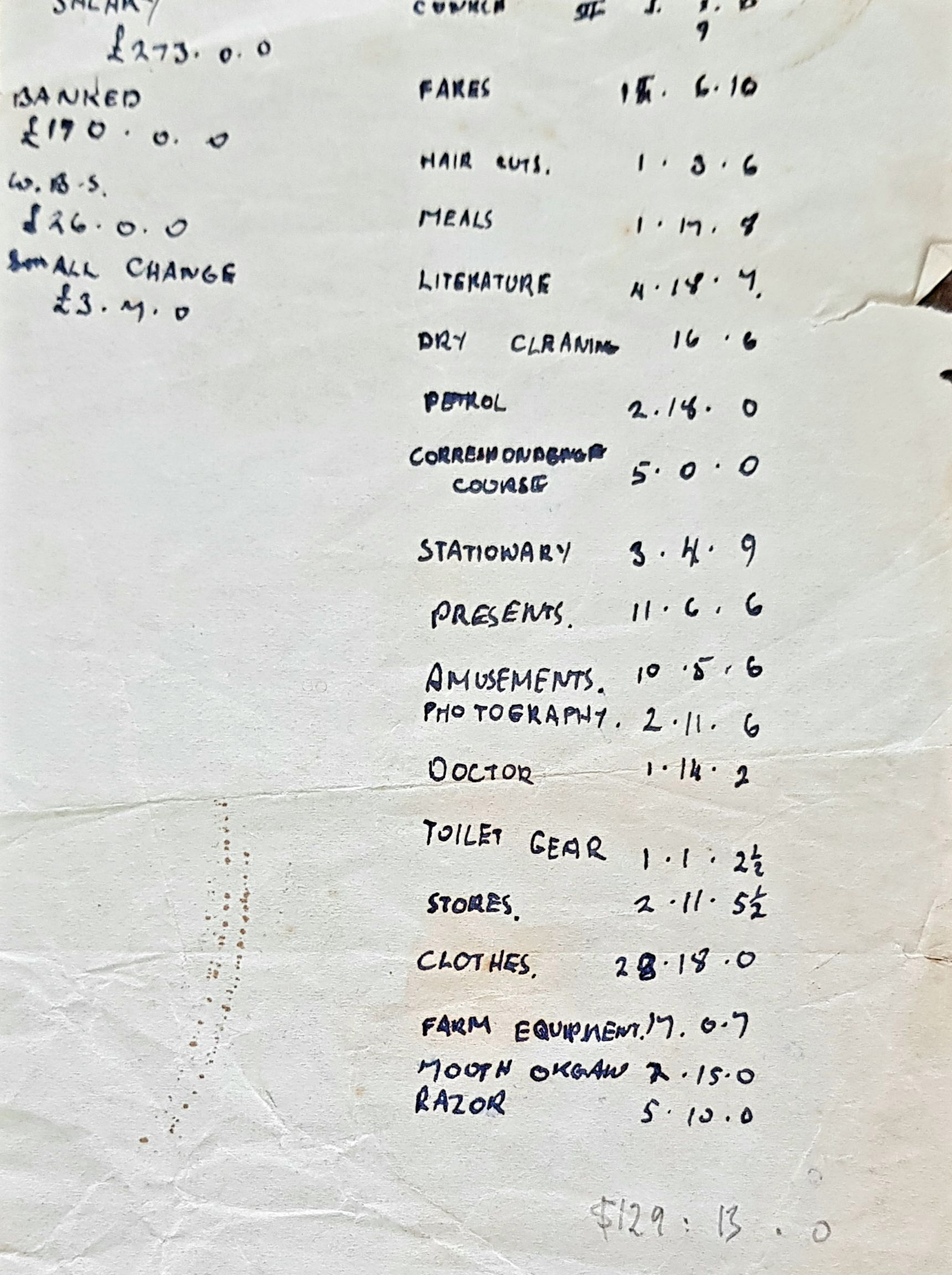

This is slightly embarrassing to me, but may be of interest. A few years ago, I discovered the document below between the pages of my old dictionary. It was my income and expenditure statement for 1956 when I was 17 years old and working on the farm in Gisborne.

I moved on after my time in Gisborne to spend 18 months at Massey Agricultural College in Palmerston North. Where I scraped through graduation with an Agricultural Diploma, I had an Austin A40 truck, a guitar, three new lifelong friends, and a permanent girlfriend who was confident, witty and attractive. We were to remain an item for two more years.

Trying to look like real farmers, and proud of our brand new hats. Me, Mick and Paddy.

Towards the end of my last term at Massey, I was offered a job by three businessmen who had bought a 900-acre Hill country farm at Kawakawa Bay. There were good tax incentives for people investing in the development of farmland and these city entrepreneurs needed a manager. Kawakawa Bay settlement is situated near Auckland, at the southern end of the Hauraki Gulf. The farm itself is at the end of a blind road about 5km from the nearest neighbour. The back part of the property fronts Tawhitokino beach which I had to myself because it can only be reached by sea, or via a steep walking track from the road.

After leaving Massey, to fill in the time until the farm property settlement took place, I took a two-month interim job chasing big money as a knife hand at the Ngauranga freezing works near Wellington. There were many colourful characters, and I could watch in awe as prime cuts of meat were pilfered from behind the backs of the white coats. I was particularly intrigued by a Maori boy and his hard-edged mate who raffled off their pay packets on paydays. This would have been a lucrative hustle, and I was highly suspicious of its veracity.

The Shoot Out at Kawakawa Bay

Farm buildings lower left. Tawhatakino beach centre left.

I wonder if you’ve ever spent a week without seeing or speaking to another human? For the first six months at Kawakawa Bay, I lived totally on my own. For company, I had a radio, some chooks, a horse, a couple of dogs, 1,600 sheep and 120 head of cattle. The solitude didn’t trouble me, but even so, Mrs Doran the local shopkeeper made me promise to check in with her once a week. If I didn’t, she would ring, and I would be suitably admonished!

We broke in 150 acres behind Tawhitakino Beach. This is a TD9 bulldozer with the blade taken off for ploughing. Obsolete now!

One day, one of the owners announced his elderly mother would be coming to live in the main house, and he hoped we would be good company for each other. The house had a beautiful view of the front beach and was used by the owners occasionally for a weekend stay. I was living in a two-room cabin about 40 meters away.

Mrs Boyd duly arrived. She would have been in her mid-seventies, we got on well, and I enjoyed our occasional chats over a cup pf tea. A couple of weeks passed, and we settled into a comfortable regime until one night about midnight my dogs started barking and a loud wailing was coming from the main house. I scrambled up the track and into her bedroom, where she was screaming and calling “I can’t breath” over and over. She was delirious and didn’t recognise me. I rang the doctor in Cleveland about 20 km away, and he said, “She’s probably having a heart attack. Get her to sip some brandy, and I’ll be there as soon as I can.”

I had no brandy so rang the nearest neighbour and after some convincing, he agreed to give me some whisky which seemed to me to be the second best option. I drove furiously back to the farm, but when I arrived, she had passed away. She’d died a painful and lonely death, and I wished I’d stayed to comfort her instead of taking off on a fruitless search for brandy!

The next night, after she’d been taken away by the undertaker and her family had returned to Auckland, I lay awake, listening to the sea rolling in, and the sound of the wind in the trees, and for the first time ever, I felt a crushing loneliness. I shed a quiet tear for Mrs Boyd that night, and the next day, returned to my solitary farm duties.

Some weeks later, I heard some rifle shots coming from the back of the farm near the Tawhitokino beach. I was annoyed but carried on with my day until at about 6 pm I saw a lost-looking young man at the farm gate. When I challenged him, he said he was looking for directions to the nearest shop. He denied any knowledge of the shooting, so I gave him directions and set about preparing my dinner. At about 7:30 pm, there was a knock at my door. The young man was back again; he pulled a newspaper from his back pocket, and pointed at his photo on the front page under the headline: Five Prisoners at Large. “This is me,” he said!

“Well, you’d better come in”, I said. He was very nervous, so I sat him down and listened to his story. His name was David Robinson; he was a ship deserter who’d been in a holding cell with the other four escapees and had been given no option but to escape with them. They’d looted a boat in the Auckland harbour and robbed two caravans in Kawakawa Bay.

They’d stolen food, several bottles of whiskey, a .303 rifle and 50 rounds of ammunition. Two of them had been drinking heavily, and they were the ones I’d heard shooting at our sheep. “Why are you telling me this?” I said. “Because two of those blokes are crazy,” he said, “sooner or later somebody’s going to get killed. I want to give myself up. The others sent me to the shop to bring them back a newspaper so they can read about what the police are doing.” “OK, fair enough; where are they now?” “Waiting up there.” he said, pointing to a small patch of manuka on top of a small ridge about 100 meters away. “Do you think they might have seen you at my door?” I asked. He nodded miserably. “OK, sit here. I’ll ring the cops, and then we’ll have some dinner. You’re not going to take off, are you?” He shook his head.

So I rang the Papakura police station.

Constable: “Papakura police station.”

Me: “It’s Ken Fife here from the farm at the end of the road at Kawakawa Bay.”

Constable: “Yes, what can I do for you?”

Me: “I’ve got David Robinson here.”

Cop: “Who’s David Robinson?”

Me: “One of the escaped prisoners. His photo’s on the front page of The Auckland Herald.”

Cop: “F—k’n Hell! Do you think you can hold him?”

Me: “No problem, but I’m pretty sure the other prisoners know where he is. The quicker you can get here, the better.”

Cop: “Roger that, we’ll come as quickly as we can!”

Me: “Yes, it’s urgent actually!”

So far, so good. I locked the door, pulled the curtains, loaded my rifle, and we sat down and ate dinner and waited. We washed and dried the dishes, and I slipped outside and removed the rotor from the US-Army jeep we owned in case they decided to nick it. I made sure I had my boots on and a jacket so I’d be able to lead the cops to where they could surround and capture the escapees. Then sat back down and waited. The prisoner wouldn’t talk much and was getting more and more jumpy.

Finally, about two hours later, we could hear a faint wailing of sirens. It got progressively louder until a stream of police cars burst into the solitude of our quiet little cove. The blue and red flashing lights could have been seen from Mars, and the really huge cavalcade of cop cars would have made the car chase in the Blues Brothers look like a funeral procession.

The parade streamed up the drive, burst through the door, and roughly cuffed and marched off the prisoner. They then commandeered my rifle and went into a huddle to plan their next move. Finally, they knocked on my door again. “We’ve decided it’s too dangerous to do anything until daylight. We’ll leave a man here to keep an eye on things. You’ll get your rifle back tomorrow”. NZ cops weren’t normally armed in those days, so I knew why he wanted my rifle. And so, with sirens wailing, the cavalcade took off back to Auckland. The escapees, of course, had long since scarpered into the backcountry.

So “The shoot out at Kawakawa Bay” didn’t actually happen, but the Key Stone Cops were proud to report the successful recapture of a dangerous criminal!

The next day The Auckland star reported, “More than 100 police and jungle-training troops are now searching the six square miles of rugged bush country near Kawakawa Bay where the escapees are believed to be hiding. Five police dogs are also in the field”.

They were led on a merry chase before the last of the escapees were recaptured five weeks later.

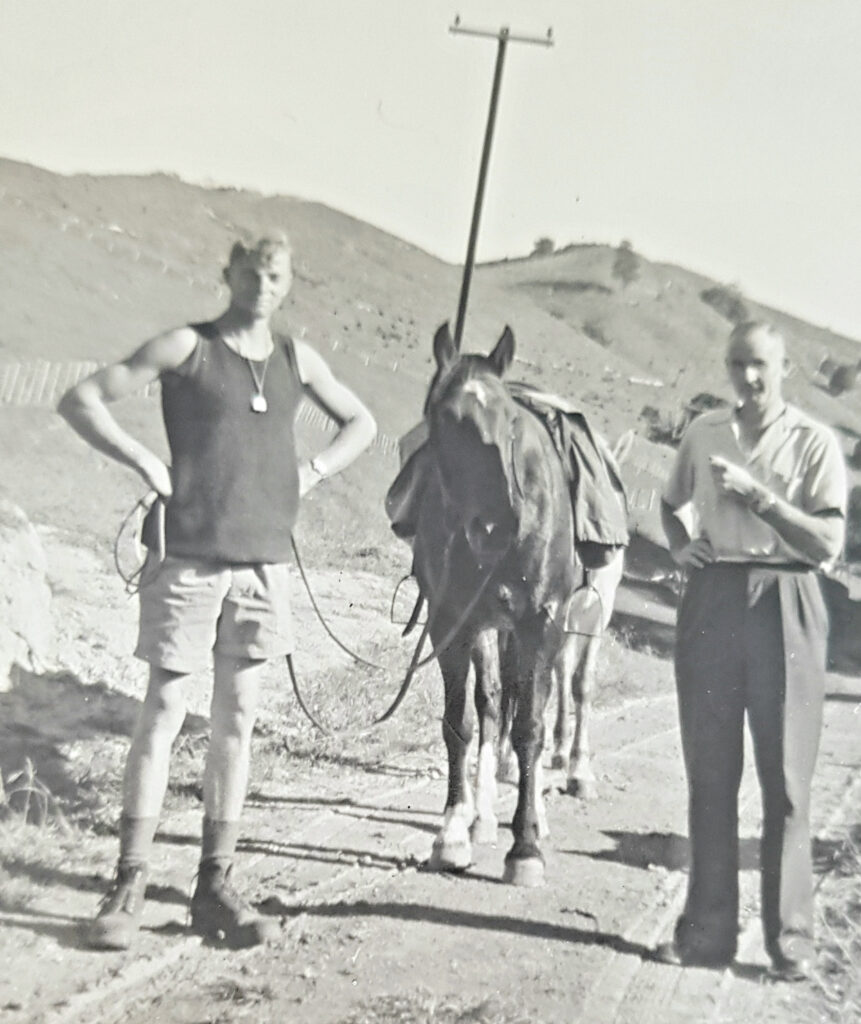

My parents have come to visit me at Kawakawa Bay. Mum took the photo.

Shortly after this episode, my employers agreed to my proposition that we hire some additional help on the condition that we run the place totally on our own.

This included the shearing, the fencing and the land development and negated the need for us to hire contractors. So my role was augmented by one of my old training farm mates, who ended up staying there for the rest of his working life.

I, on the other hand, decided to move on after 17 months. I didn’t get on particularly well with one of the owners, and we had a disagreement over what constituted a fair wage for a farm manager.

Greener pastures beckoned, and with a spring in my step, I headed off to live in the city.

City Life

I moved to Auckland and began to scan the papers for interesting jobs. An added bonus was the arrival of my girlfriend to start a hairdressing course. This meant we no longer had to negotiate the 500 km distance between Palmerston North and Kawakawa Bay.

My first job was employment as a “Stockie” at Westfield freezing works. It paid well and gave me security and time to search for my next career move. I joined a small team whose task was to take charge of livestock on delivery and drive them through the yards and up the race to the slaughterhouse. We were assisted by the trained Judas sheep. These animals were used in most abattoirs to lead sheep towards the smell of blood, which they are naturally uneasy about, and on to their eventual fate.

Lambs to the slaughter as it were.

After a few weeks, I was elevated to the chain gang and became a “Pouncer” at a much higher rate of pay. And no, Pouncer is not a misprint; the term Bouncer hadn’t been invented. Workers on the heavily unionised chain at freezing works had better conditions, shorter days and much higher wages. I won’t go too far into the gory details of what my job entailed; suffice to say the Pouncer stands at a bench between two others, the “Shackler” and the “Sticker.” A lever is pulled, a single sheep slides down the chute, and the result in about 5 seconds, is another lifeless body hanging, kicking, by a hind leg from the moving overhead chain. By the time the next animal slides down onto the bench, the skinning and eviscerating process has started by the next slaughter men down the line. Did this concern me? Not really; butchering animals on farms for consumption by farm staff and working dogs is a regular farm chore.

Finally, after about two months, I saw an advertisement for the perfect job. It was for a Land Development Field Officer in the King Country, which is situated in the centre of the North Island. The employer was the Lands and Survey department, and the job involved supervising the development of four large blocks of government land for eventual subdivision into viable farms for deserving young farmers.

This job ticked all the boxes for me, and after two interviews, my application was accepted. I was warned I was by far the youngest in this position they’d ever employed; I’d better make a go of it!

The position gave me everything I could ever hope for. I had a great boss; I loved the work, and I loved the remote and wild nature of the country we were developing. I loved driving slowly through seldom used logging tracks on the way to and from work, always on the lookout for a deer to provide venison for the pot.

Life was good, but I didn’t know my world was about to be turned on its head.

Coming of Age

There was a reunion planned in Auckland with a few of my Massey mates. I decided at the last minute I would be able to attend. The gathering finished up earlier than I’d expected, so I rang to talk to my girlfriend, who lived in a YWCA hostel. I was told she’d gone out to the pictures and was expecting to be home around 10:30 pm.

She wasn’t home when I called, so I waited outside in my car, which was now a 1953 Chevrolet. It was a light green colour and easily identifiable. It had been a long day after the drive to Auckland, followed by a few drinks with my friends. I was dozing when I was awakened by a rap on the window. The night was dark, I opened the door, and by the time I got to my feet, I had a broken nose and a rapidly closing left eye.

My girlfriend was getting out of the car parked behind, screaming. I never got a good look at my assailant, there were no words spoken, but less than two minutes later, I was speeding away in the dark, stricken by the bitter realisation I wasn’t welcome. My girlfriend had transferred her affections to someone else and hadn’t thought to tell me.

As for the shipwreck left behind. The erstwhile “Sir Galahad” was lying on the road, and he wasn’t getting up. My girlfriend was sobbing and crying, no no, no, over and over! Lights were going on in the surrounding houses, and it would only be a matter of time before the sirens started. I was now on the long two-hour drive back to Taumaruni. My shirt was soaked in blood, mostly mine. Looking back, that was the moment that turned me into an adult.

Footnote. Sometime later in 1964, about five weeks before my marriage to Rosaline, a letter arrived at the office in Alexandra. The writing on the envelope was familiar. It was the first communication to take place between my ex-girlfriend and me since the fall of “Sir Galahad”. The message inside was brief. “I’ve heard you are thinking of getting married. It’s not too late for us to get back together again. What do you think?”

I allowed myself a smile. We’d had a lot of good times, and there were fond memories. But those were our teenage years, and I was now looking forward to a bright new future. The letter was best left unanswered.

Ken Fife

October 2021