INTRODUCTION

Our Mum on shopping day with my sister, Lorraine, 1938.

I was born in Wellington New Zealand in 1939 and later that year on 5th September, New Zealand’s first labour prime minister, Michael Joseph Savage, got wind of my arrival and was so depressed that he rang Neville Chamberlain and they both decided to declare war on Hitler.

Savage died six months later in 1940. The date of his death was March 27th. the first anniversary of my birth.

NZ was now at war, disproportionate numbers of young men were to serve abroad, and for most families, these were years of austerity. Our parents were far from wealthy, and in the early years, we lived in a State Advances house in the Belmont Hills near Wellington.

My sister Lorraine is two and a half years older than me and my sister Margaret, eight-years younger. Dad held a clerical position in the Internal Affairs department, and our parents worked tirelessly to keep us happy and well provided for.

When I was old enough to understand, the war was an ever-present shadow. Dad’s brother Stewart was an Anti Aircraft gunner and was strafed and badly wounded during Rommell’s campaign in the Western Desert. This was hard for the family particularly as his mother (Nanny Fife) had already lost her brother John at Gallipoli in the first world war.

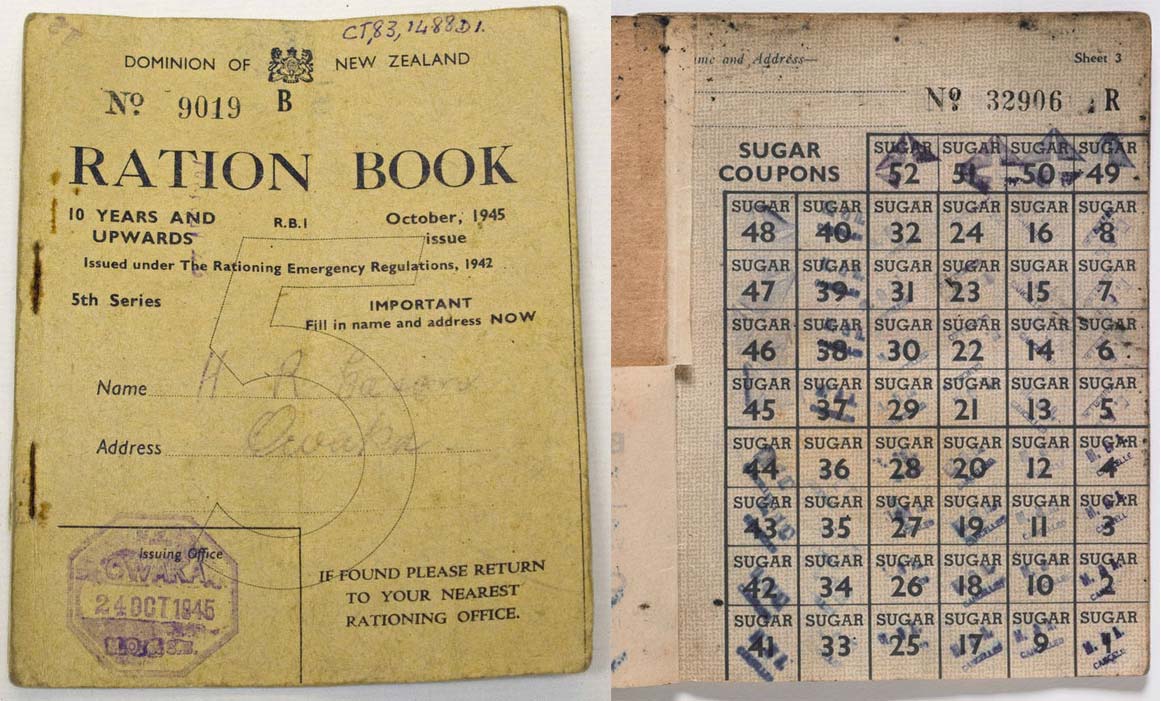

Ration books were issued through the Post Office to the head of each household and became an essential part of daily life. Generally, women were in charge of the household’s ration book, as they tended to do most of the shopping. The coupons were cut from the books by retailers.

Clothing and footwear were rationed in May 1942. Every household was given 52 clothing coupons per year. A man’s three-piece suit for example, which Dad had to have for work required 16 coupons. A woman’s dress required four to six coupons – either as a store-bought dress or the material to make it.

Growing up, I remember thin brown ration books with postage stamp-sized coupons for basic foodstuffs and clothing. Petrol coupons were particularly precious but of no use to us as we didn’t have a car.

Blackout curtains were essential at night. Once when shopping with my mum in Wellington, the air raid siren sounded, and we all ran into an underground shelter. It was only a practice run. I have a vivid memory late in the war of mum and dad huddling over the radio listening to a ranting diatribe by Hitler. His staccato voice was loud and threatening, and the adults were silent as the translator hinted at tough times ahead.

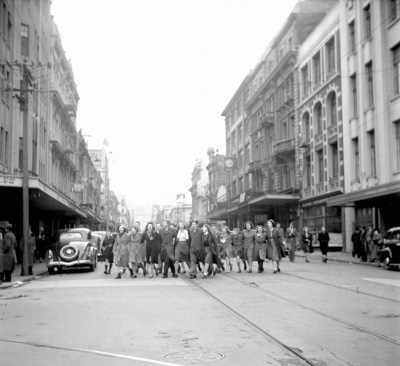

Victory over Japan Day Wellington August 1945.

Eventually, on 15th August 1945, victory over Japan (VJ Day) arrived. I was at school when news came through that the war had ended. This was a wonderful day. We were sent home, and our family and friends congregated in Wellington, where people were dancing around holding hands in the street. Relief and renewed hope for the future was palpable even to me as a child. The wonder of the bright city lights after years of blackout is still a vivid memory.

In the early post-war years, mum as a member of the Women’s Institute was delivered sack loads of army uniforms. These were piled in heaps on the veranda, and she spent days preparing them for recycling. Buttons and epaulettes were removed and rank insignia unpicked. As kids, we riffled through the clothing searching fruitlessly for bullet holes and hopefully even blood stains. But there weren’t any, and we soon got bored.

In the ensuing years, army surplus stores had a big appeal to me as a teenage boy. There were exotic items for sale, such as hand grenades, bayonets, tin hats and commando knives. Some of the grenades had slots cut in them to turn them into money boxes. The gunpowder had been removed and when the pin was pulled the lever flew up with a satisfying click. There were army pup tents, tins of bully beef, hard-tack biscuits (like little concrete tablets,) and much more. The country was awash with standard army-issue Lee Enfield .303 rifles. My father came home with one for me as a surprise on my 15th birthday.

At my school, Hutt Valley High, boys in the 5th form had to attend army cadets. This took place in the school playing fields once a month so while the boys were being trained to become the next generation’s canon fodder, the girls attended home economics classes.

Wellington College School Cadets

On Army cadet days, we attended school dressed in khaki shorts, battle jackets and army hats. On special occasions, we rode to and from school on the bus or train carrying our rifles. Lee Enfield magazines hold 10 cartridges. For the cadets, the cordite had been removed, and nickel bullets were replaced by wooden ones. We were taught the rudiments of rifle maintenance and how to reload magazines under pressure. We marched and did parade ground rifle drills while the 6th form boys were taken to a rifle range and taught to shoot Sten guns with live ammunition. WW2 Sten guns were Automatic weapons and a precursor to modern-day AK47s.

Lee Enfields were a good utility rifle for their time but had one dangerous flaw. If they were loaded and cocked and you bumped the stock sharply on the ground, they would fire. This can happen even when the safety catch is engaged, as it did once with me when I was walking behind a mate whilst deer stalking. I slipped on a rock, thrust the rifle butt onto the ground to save myself and nearly shot my friend in the back!

My cousin John told me one day at his school Wellington College, one of his mates substituted a couple of the wooden bullets with live cartridges pinched from his father’s draw. This must have provided a good giggle among him and his mates on cadet day. But unfortunately, one of the rifle drills is to ground your rifle smartly, push the barrel away from your body, and then adopt the stand-at-ease position. This kid must have dropped the rifle a little too robustly, and it went off. You can imagine the noise! The bullet whistled over the instructor’s head, resulting in chaos and triggering a front-page story in the Wellington Evening Post. I would have loved to have been there!

My early teenage years were a happy time. I wasn’t motivated academically, having decided from a young age, that I was going to be a farmer. I was an outdoors person and spent a lot of time wandering around the bush or catching lobsters in the creeks. I trapped possums and sold the skins, collected and sold bottles and worked after school in our family’s milk bar. I was a keen boy scout and benefited enormously from my time in that excellent organisation.

I guess I was about 13 when I had to sit for my First Aid exam as the final step in the achievement of the First Class Scout Award. The examiner held a very senior profile in district scouting, and I cycled to his house, arriving just after dark. I was led through the sitting room where his wife was sitting on the sofa knitting. She smiled kindly as I was ushered into the office in the adjacent room where the test began. It was going well, and we came to the topic of pressure points. The hypothetical wound was, you guessed it, on the examiner’s upper thigh. He said, “I’m bleeding to death what do you do?” I said, “Target the pressure point in the groin area.” With great severity, he pointed out this was not a theoretical exam, “Get on with it.” I tentatively pushed near the appropriate area and encountered his erection. I pulled back uncomfortably, he glared at me and said, “If you are going to save a life, you need to press a lot harder than that.” He adjusted himself, scribbled some notes for my scout master, which he passed to me and said with an expressionless face, “Congratulations, you’ve passed your exam.” I rode home happily in the knowledge I was about to become a First Class Scout, not really understanding I’d just had a brush with a pedophile.

Our Grandfather, William Fife, was lighthouse keeper at the Pencarrow Heads lighthouse on Wellington Harbour. During the war, I spent long periods living there, whilst my sister Lorraine was sent to our maternal grandparents in Hamilton.

Our Grandfather, William Fife, was lighthouse keeper at the Pencarrow Heads lighthouse on Wellington Harbour. During the war, I spent long periods living there, whilst my sister Lorraine was sent to our maternal grandparents in Hamilton.

It was wartime, and mum had been recruited by the Manpower Officer, who, after 1943, had sweeping powers to recruit civilians into essential industries. In October 1942, minimum weekly wage rates were fixed at £5 10s for men and £2 17s 6d for women. This equates to roughly $10 and $6 a week in today’s currency.

Women were invariably paid less than men even when doing the same job. There was little resistance to this inequality.

William Fife. Lighthouse Keeper with our Grandmother Elizabeth

Grandfather was at best grumpy and at worst scary. I don’t recall much warmth from him, but Nanny Fife was always there to make sure I was a good boy and kept out of his way.

His background had been in the pharmaceutical industry. He had a large medicine chest in his bedroom, which was a source of angst to us kids. The maxim, “Little children are to be seen and not heard,” definitely prevailed.

Excessive noise, dirty fingernails, or other misdemeanours resulted in noses being pinched and the forceful administration of castor oil.

And yes, it happened several times, and I can’t overstate the ghastliness of this experience when you are little!

Pencarrow Lighthouse – Built 1852.

Just before he died, in his late 60s, and when I was nine years old, he and I had a pleasant conversation about books. He told me, “It’s important to read as many good books as you can and even more important for you to always remember the names of the authors!” And to this day, I’ve treasured this conversation and have tried to follow his advice. This was the only pleasant discourse I can ever remember having with him, actually.

In 1960 the lighthouse was decommissioned but still remains a tourist attraction. The brochures state, Pencarrow Head is a rugged environment, and the weather can be wild and highly changeable with severe wind. Please check the weather conditions before you visit. This is not an exaggeration! The Sou’West wind funnels through Cook Strait, and I remember listening to it rattling the trees against the corrugated iron fence from my bed at night. There was no electricity, we used candles and kerosene lanterns, and to warm the bed, my grandmother heated a brick in the coal range and wrapped it in a tea towel.

Goods Delivery Pencarrow Heads

The site of the keeper’s quarters and lighthouse was situated 8km from the seaside town of Eastbourne. There is a gravel road in now, but in those days, the end of the main road and the commencement of the riding track were locked by a big white gate with a “Keep out by order of Government” sign. So you either walked, rode on horseback, or came in from the sea.

We were self-contained, with a vegetable garden, a milking cow, some chooks, and two horses for riding or carrying supplies. My grandmother baked bread and scones daily.

Sitting on the trolly used to winch diesel to the foghorn hut. Lorraine and me on the left, and John Beverage, a friend, on the right.

Sometimes my father visited at weekends. He had a spear with a long manuka shaft. He must have been very agile and used it to pole-vault from rock to rock to spear Butterfish.

These fish are native to the Cook Strait area and are considered a delicacy. Crayfish and Paua (Abalone) were reasonably plentiful when the tide was low enough to get to them, and at other times Blue Cod could be caught from the jetty.

The lighthouse was built in 1852, and it wasn’t until 1871 that the government erected two residences for the Keepers. Before then, they had to make do with ‘temporary accommodation’. It must have been a miserable posting. George Bennett, the first keeper, had a wee girl, Eliza, who died of consumption aged two and a half years.

A subsequent visit by the authorities led inspector C R Carter to report, “Her death can probably be attributed to their poor living conditions.”

Her lonely resting place is enclosed by a white picket fence on an exposed promontory overlooking the sea. When I asked who was in the grave, my dad said it was a little girl who stood too close to the cliff and fell off. I stepped back quickly.

Until the discovery of penicillin, death from consumption or TB as it is now known, was all too common. We had two second cousins, Kevin and Emmett, who died of the same disease during a pre-war epidemic They were only in their early twenties.

The original lighthouse is on top of the hill, The Fog Horn enclosure is halfway down, and the replacement Lighthouse at the bottom near the beach.

Pencarrow, like many lighthouses, was a two-man station. This meant a gruelling regime of night shifts with each man serving in the lighthouse alone. Manning the light was not ‘a comfortable job’. According to Maritime New Zealand’s information on lighthouse keeping, ‘keepers were allowed only hard, straight-backed chairs in the light room, and no radio which would distract them or send them to sleep’.

Beaglehole notes that the provision of a chair and desk was actually an ‘improvement’ on earlier conditions.

The duties of keepers’ wives were not recorded in any detail, but they were no less arduous. Wives cooked, washed and cleaned in primitive circumstances, and after the correspondence school was established in 1922, often supervised their children’s education. Source Wikipedia

When I lived there, the two-man regime was still extant. The other keeper was Mr Simpson, who, when on duty, lived there with his wife and children. I don’t know how the shifts were organised, but I don’t think the two keepers were often on station at the same time.

The First lighthouse was erected on top of the hill overlooking the entrance to Wellington Harbour, but in time a second structure had to be erected lower down because at Pencarrow, when it isn’t blowing a gale, there can be fog, and the light was often obscured. In 1935 a new automated lighthouse was erected at nearby Baring Head, but there was still an ongoing role for keepers at Pencarrow to operate the fog horn.

Not the Pencarrow foghorn, but the original would have been similar.

There had to be a 24-hour watch kept, and when bad light or fog obscured landmarks for mariners, the foghorn was activated.

In the fog horn hut pictured on the cliff above, I remember two large steam engines necessary to drive the air compressor that produced the warning signal. This system gave a mournful three-second blast every minute.

When the fog signal was finally automated in 1959, it took away the need to have staff permanently stationed at Pencarrow. In 1960 the last keeper was transferred from the station, and sadly, three years later, the station buildings, including the keepers’ residences, were all demolished.

Our grandfather died in 1948 in his late 60s. He seemed a sad man to me, and I wish I’d been old enough to get to know him. Our grandmother, formerly “Lizzie” Jones, was a humble, selfless person who had endured a hard life. She lived until her 79th year and was much loved by her many grandchildren.

Ken Fife

September 2021