e returned to NZ to be faced with a tsunami of problems which by 1983 resulted in the dissolution of our marriage and an end to my life as a farmer, but I’m getting ahead of my story.

I was born with an innate resilience so coped well with the dramas on the Fijian cattle ranch. Most of the time I enjoyed the challenges and the satisfaction that comes with solving problems, and life in Fiji had many consolations.

Expat friends in Suva had bought a cruising catamaran and we spent occasional weekends sailing or working on their yacht. Over the past two years, we had hosted politicians and officials from both NZ and Fiji. We had cajoled NZ army helicopters into assisting with mustering and fence line laying projects. We sipped cocktails on a NZ Navy Frigate and were interviewed by both Fiji radio, and TV NZ for their 60 Minutes program.

The good outweighed the bad, but the relentless hours, the isolation, and the necessity for our family to spend so much time away from each other had taken its toll. We were big fish in a very small pond, now it was time to return to New Zealand.

Cairn Peak

Our farm was a picture when we arrived home in January 1981. It was early summer, there had been plenty of rain, the hay sheds were full, the crops were looking promising and the pastures were beautifully green with stock feed in abundance. John Robins our interim manager, together with our staff, had done an excellent job.

We were presented with the stock performance figures and pleasingly, 6,000 lambs had been produced from our 5,000 breeding ewes, and the long-term weather forecasts pointed to a good fattening season for our lambs and beef cattle.

Since our acquisition of the farm in 1964 Cairn Peak had transformed from an ugly duckling to a desirable property, and our burgeoning forestry business had transferred 2,000 acres of marginal land into a profitable industry.

Bill Piercy, together with Rosie and myself had been equal business partners since 1966. Bill had a 50% share, and we had 25% each. I was the resident manager and Bill was a public accountant running his own business in Gore, 70kms away. Up until now, we’d had an easy relationship, and I had run the property without interference. However, our partnership agreement was due to expire on 1st June 1981 at which time it would be up for renegotiation.

Six years earlier in June 1975 I had written to Bill notifying him, that on the expiry of the agreement Rosie and I would be exercising our option to withdraw. Bill had not responded, so now with less than 6 months to go, we had some negotiating to do. Over the intervening years, I had obtained two qualifications. I was now a registered Farm Management Consultant and a member of the NZ Society of Farm Management. I had also passed the exams entitling me to practice as a Registered Rural Valuer.

I called a partnership meeting and tabled an aerial photograph of our sprawling property. I had drawn a line bisecting the photograph and explained to Bill why I thought this was a fair attempt at equally dividing our holding. The individual farms on each side had a fair balance of flat and hilly terrain and each had appropriate farm infrastructure. To back up the integrity of the offer I said I would be comfortable for him to choose which of the two properties he preferred to own. I could tell by his demeanour that up until now he’d never confronted the reality that our partnership had run its course. He blustered and said the offer was ludicrous. He would draw a line on the map in due course, and that he would also have first choice of which parcel would be his.

Trouble was brewing!

Some weeks later he produced a map indicating an insultingly unrealistic portion to be allocated to us with the balance of the title to revert to him and his family.

That was the last time we engaged in a cordial conversation.

For the next 6 months, Rosie and I were to live on the farm under a cloud of disillusionment as Bill’s lawyer and our lawyer attempted to broker an outcome to keep us out of court.

It was finally agreed that each party would appoint a valuer, and an independent arbitrator would be engaged if the valuers couldn’t agree. Once the value was settled, Bill would have first option to purchase the going concern and if he defaulted, Rosie and I would be given the same opportunity.

The valuation went ahead and the valuers agreed, without the need to resort to arbitration. Bill had 90 days, and settlement was set for 23rd December 1981. In mid-October, his lawyer wrote with the news that Bill was adament he had the finance organised for settlement day and he preferred I step down as manager,and leave the farm immediately. We were thankful for closure and with mixed feelings, packed up and moved to our holiday house in Manapouri.

We weren’t surprised when on 23rd December Bill couldn’t come up with the money, but he said it was a technicality, he needed another 30 days and reluctantly acknowledged this would trigger the 17% late payment penalty fee.

Finally, at 4 pm on 25th January 1982, the phone rang in Manapouri. Our solicitor said, “congratulations, you are now millionaires, what do you want me to do with the money?” I was 42, Rosie was 39, and for the first time since I was 15 years old, I was not involved in the farming industry. I was unemployed!

Final Outcome

Bill was not a farmer. He’d had a romantic notion of riding stock horses, and comparing notes with other farmers on a Friday night in the Dipton pub. He’d put two of his sons, both town boys, through a diploma course in an agricultural college and the family battled on for a few short years before finally succumbing to a mortgage default. The property has since been broken up and sold to neighboring farmers, and sadly at a very young age bill succumbed to cancer. ,

Our falling out had produced no winners.

Moving on

Before our sojourn in Fiji, we had purchased a holiday house in a sleepy village called Manapouri which lies adjacent to the Fiordland National Park. Lake Manapouri is surrounded by mountains that are snow-capped in winter and the lake itself is frequently draped in wispy mist which makes it hauntingly beautiful.

According to Wikipedia, “Fiordland National Park covers an area of 12,000 square km, making it one of the largest national parks in the world.

Lake Manapouri

It is famous for its deep fiords, stunning alpine lakes, waterfalls, rainforest, and unique wildlife. Within the fiords, you can find dolphins, New Zealand fur seals, fiordland crested penguins, and the occasional whale.” There is no mention in the brochures of the ecological threat to the rain forest caused by overgrazing from introduced animals, particularly, possums from Australia, and red deer from the UK.

In the 1970s the establishment of a venison export market, created a new industry in Fordland, and a potential solution to the noxious animal problem. There was a ready sale at mouth-watering prices, for venison shot by ground hunters, and by shooters in helicopters, scouring the mountain ranges and adjoining tussock country.

The introduction of rigorous meat inspection standards eventually slowed down the venison trade, but the recovery industry still thrived, as focus shifted to the capture of live deer from two sources, trapping in the rain forest, or netting from helicopters in the tussock country above the bush line.

Three of us shot these deer in the rain forest over three days, carried them out on our backs to the safe in the picture, where they were transported out to the lake by the pack horses. Hunter Shaw on the left was a professional meat hunter, I’m holding the horse.

Deer Trapping

My Friend Lance Shaw was a deer trapper and I helped him occasionally with building traps and recovering captured animals. These traps were made of wire netting too high for the deer to jump over. The pens when built were about 20 yards long, and constructed so that deer using the game trails, couldn’t see the netting hidden among the trees. When they entered, they would trip a wire which released counterbalances holding the gates suspended overhead. Lance would check his traps once or twice a week depending on weather conditions.

Captured animals were wrestled to the ground, blind folded, and injected with the sedative Vetcalm. This neutralised their anxiety for long enough to be coerced into walking to the boat. Wrestling with an adult antlered deer wasn’t a job for the faint hearted, even when working in pairs. On one occasion one of lance’s helpers was attacked by a young “spiker” and hospitalised with a serious stomach wound.

My first business enterprise after settling in Manapouri was to act as a middleman between a helicopter company and deer farmers. I purchased live animals straight off the chopper and transferred them to a local deer farmer. He ear-tagged them, and looked after them until they were accustomed to fenced paddocks and ready to sell-on to farmers.

Fiordland National Park

The Fiordland Triangle

There is a saying in rural areas in New Zealand that could have been coined specifically for Fiordland in the seventies and eighties. “There are old pilots and bold pilots, but there’s no such thing as old bold pilots.” There were fortunes to be made in the venison and live deer capture industry, but as the deer got fewer and wiser, the choppers had to fly closer and bank and turn quicker, and the margins grew too small for safety.

I lived in Manapouri for a little over two years and was acquainted with a number of people who lost their lives or were permanently injured in air accidents. They were larger than life characters, with exotic nick names,, and outgoing personalities, who you’d have a beer with one night, and be reading about in the paper the next day. I was personally involved with two attempted recovery missions. A Jet Ranger Helicopter with a pilot and two shooters aboard, left Te Anau at daybreak and flew low over Lake Manapouri into the mist. For some reason it flew at speed straight into the lake and all were lost. The next day, together with the Chopper owner, Lance and I spent several hours trawling the lake in a spot where a small oil slick had appeared. We snagged something but weren’t able to bring it to the surface. The lake is very deep and as far as I know the wreck and the remains of the deceased are still there.

It’s the same with the Cray (lobster) fishing industry. The West coast of Fiordland is bleak, unforgiving, and pummelled by gale force winds. The Crays are plentiful when a run is on, and fortunes can be made if you can get your cray pots to places where other fishermen won’t go. A local fisherman and his young deckhand didn’t return home one night and Lance and I at the request of his wife, left at daylight the next day, hoping to find them waving to us from the shore. What we found was a pitifully small amount of matchwood scattered along a gravelly beach, and an empty twisted cray pot with one rubber glove in it. His fishing boat had most likely been hoisted by a monster swell and dumped from high onto a submerged rock which wiser fishermen knew to keep away from. Their bodies and the remains of the fishing boat were never found..

Shaylene

Shaylene was a 52-foot cutter rigged sloop, owned by Les Hutchins the owner of Fiordland Travel and Les knew I could be called on to crew for him at short notice. One of our more interesting trips was a charter by National Geographic who were planning to publish an article on Captain Cook’s discovery of New Zealand in 1776. Cook had explored, named, and mapped the principal fiords in Fiordland and we had the privilege of retracing and photographing this part of his historic voyage. The American photographer chartering Shaylene, realising there were bunks to spare invited some female professional circuit tennis players, to join the cruise. These passengers, including the National Geo photographer, all proved to be prima donnas of the highest order and it was a relief when they finally disembarked.

A few months earlier Les had invited Lance and me to help him crew Shaylene on a voyage up the western side of NZ, around Cape Reinga at the top, and down into the Bay of islands. We were to be accompanied by one of Les’s employees called Des Arthur, which was a bit worrying, because he was known locally as “Disaster.”

We set out from Bluff, New Zealand’s southernmost town, around midday on a blustery sunny day. We were headed for Milford Sound and Les said a front was forecast to the northwest, but we had a fair wind and with luck should make Milford before the worst of it arrived.

The run along the bottom of the South Island went well but when we rounded the cape and turned north, the sea became more turbulent. We shortened sail and headed into a strengthening wind. By the time darkness fell the gale had lifted to a steady 40 knots and was gusting much higher. We dropped the reefed main, raised a storm jib to help keep her head to wind, and motored on. We were sharing two hour watches, one man on the wheel and the others harnessed into their bunks. By now all except Les were seasick but we still had to take our turn at the wheel, and to assist on deck if called by the man on watch. In the end it was easier to remain on deck while Shaylene battled on. By about 10 pm the wind was sitting steady on 60 knots and gusting to 90. We were now in the grip of a category one hurricane and the huge swells at times towered above us. There would be a short period when they’d come in a regular pattern but without warning we’d be knocked down by a massive breaker from a different direction. and with the yacht struggling to right itself, there’d be another bigger wave that would knock us flat.

Below decks, everything not tied down or locked away came adrift and the main cabin floor was strewn with objects sloshing around with every erratic movement of the ship. The crashing of this detritus, and the juddering of the ship were drowned out by the screaming of the wind in the rigging.

Several times that night the railing was in the water and the spreaders on the mast almost touching the sea. Finally in the wee small hours, Lance and Les who were the real seamen, plotted a safe passage through the rocks studding the coast near the mainland, and we limped into the safety of Milford sound. We spent two days recuperating before Les’s daughter Robyn joined us and we set sail again for the Bay of Islands. The weather had settled by the time we ventured out to sea and 6 days would pass before we were to see land again.

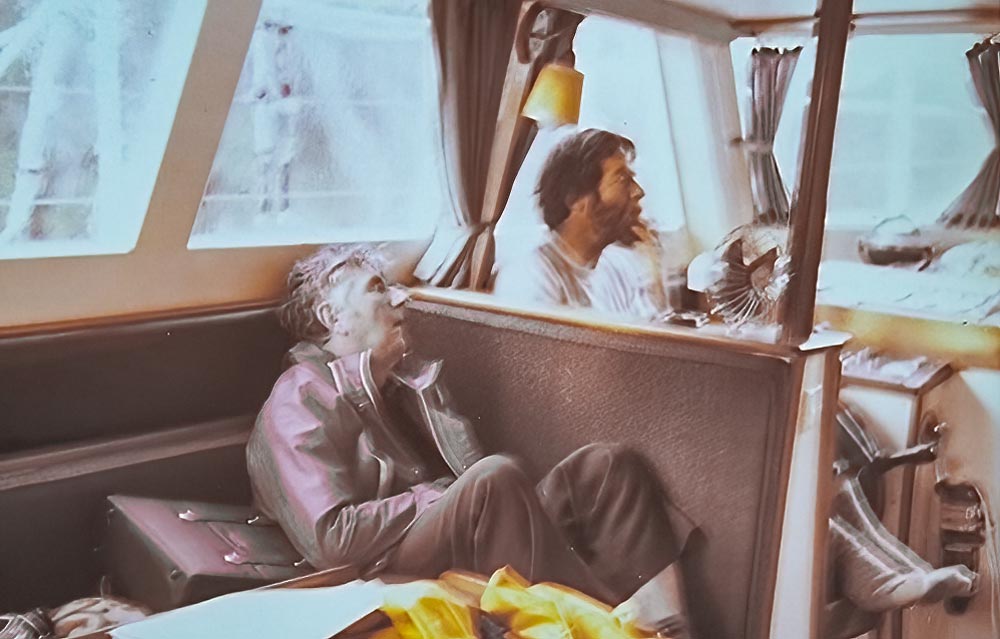

Worn out crew, finally at anchor in Milford.

The next leg was relatively uneventful except at daybreak one morning, when Les went on deck to relieve Disaster at the wheel. He saw Des had earphones on and was listening to his tape recorder with his eyes closed. Les noticed two other things. There was land on the horizon where no land should be, and Des’s magnetic tape recorder, was nestled snuggly alongside the ship’s magnetic compass. Les plucked the recorder out of the cockpit, Des woke up, and Les steered a safe course out to sea again. And what was Disaster listening to? Of all things, a recording of Winston Churchill’s funeral.

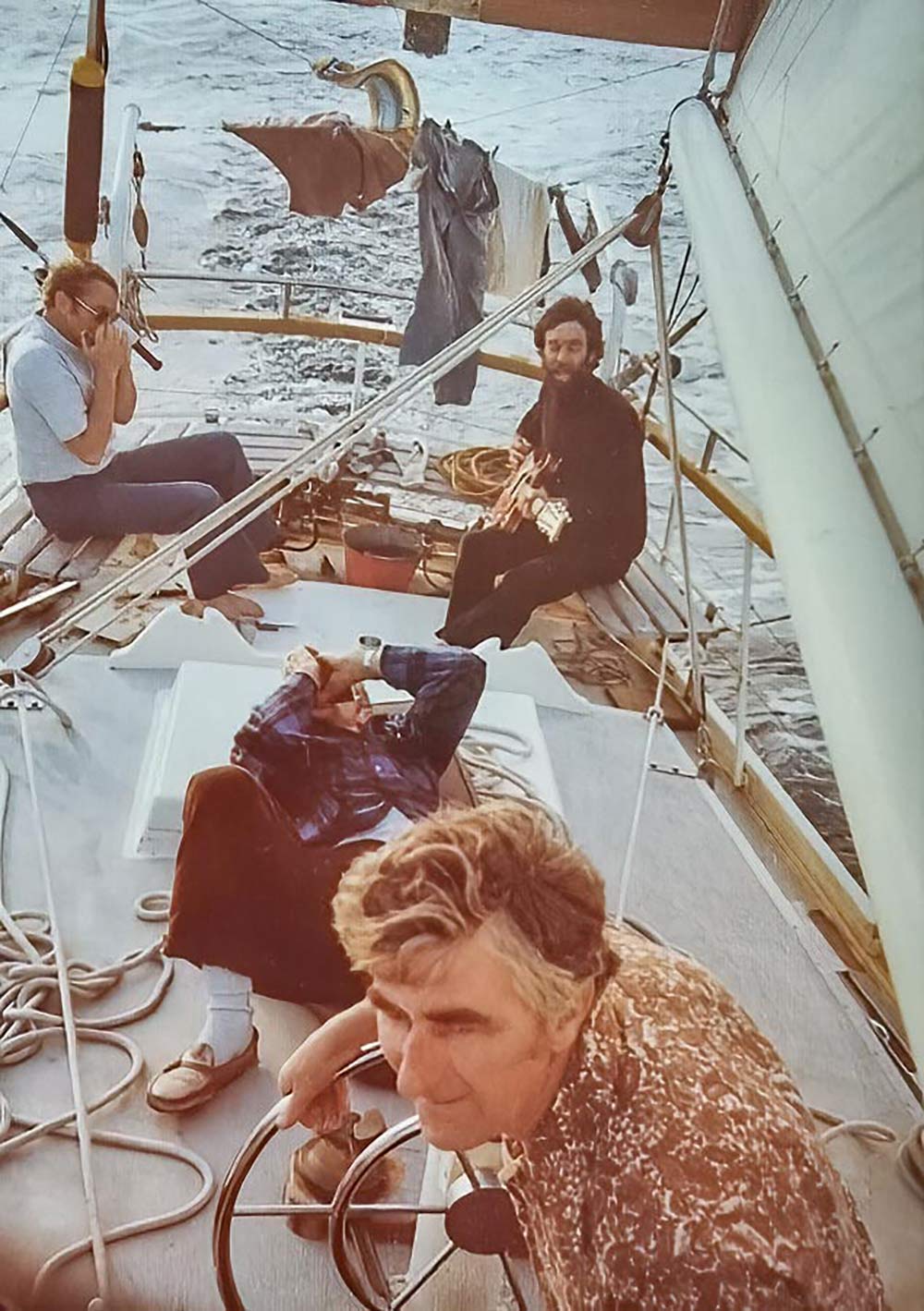

Cruising. Les Hutchins at the helm, and from left, me, Des, and Lance with guitar.

There was very little sleep to be had on the final night. The weather was warm, we were making good time, but we were approaching the shipping lanes. We rounded Cape Reinga a little after midnight and made our way south to our anchorage in the bay at Russell in The Bay of Islands.

I rose early while the others were sleeping. The sun was inching over the horizon and I watched the night slip away. There was a warm summer breeze and it was going to be a beautiful day. The memory of this special moment is as vivid now as it was more than 40 years ago. There were three dead flying fish on deck, I selected the biggest and tossed the other two overboard. I now had bait which I attached to a rod and in twenty minutes had caught two gurnard big enough to provide a small portion of fresh fish each for breakfast. I stowed the fishing gear and reflected on how great it was to be alive, while around me the sea birds and other inhabitants of Russell, came slowly to life.

Crossing The Ditch

Chapter 11 of my story will be published shortly. It covers my final months in New Zealand before I decided to start a new life in Australia.

Very interesting as always Ken! Reminds me of my brief career as a deck hand on a pair trawler . I was the mug who had to jump from one deck to the other in the dead of night in choppy seas. I lasted six weeks . A life at sea ? No thanks I’m a landlubber! Brian is a sailor and has a deep sea fishing boat in the Bay of Islands . I am looking forward to hearing about your career change . Stay well!

Hi David. That’s another part of y our life I didn’t know about. Take care – Ken

What another extraordinary instalment, Ken! And what an incredible life you’ve lived so far!

Thanks for your technical skills Peter

Very interesting Ken so many stories, you are a “Jack of all trades” for sure. Love reading your life adventures

Thank you Michelle. I hope life is treating you well.l

What amazes me about your stories is how easily we assume a complete picture of a person, and how easy it is to be wrong. You are the quintessential Renaissance man.

So visceral Ken.

Fascinating and engaging reading.

Thanks Hermes. Hopefully we’ll see you soon

Loved it. and the pictures are beyond stunning

Hi Alison. You must be proud of your new Portuguese citizenship. 🙂

Never a dull moment Ken. Great true stories, full of adventure and mostly good memories.

Magnificent photos!

Looking forward to your next chapters.

Thanks guys

Fantastic reading Ken. Your life has certainly been full of adventure. We’re so looking forward to sharing more adventures with you and Lee in September

Hi Chris and Joyce, We’re primed and ready for our reunion in Septemeber. It’s been a long time.