After landing in Melbourne, I ticked the box on the immigration form to indicate I intended to remain permanently in Australia. The customs official showed no interest, he scribbled something on the card and shooed me through to the arrival hall.

My first impression as I walked outside was the pleasant summer temperature and the superior quality of the vehicles in the car park.

Within 3 weeks Lee and I had found a house and paid $62,000 cash for it, much to the delight of the vendor who politely asked if we’d won tatts lotto or something. We signed on the condition we could take possession within 7 days. The house was in a middle-ring suburb about 30 minutes North of the CBD and for the first time in my life, I had a permanent address in a street of houses.

Within 3 weeks Lee and I had found a house and paid $62,000 cash for it, much to the delight of the vendor who politely asked if we’d won tatts lotto or something. We signed on the condition we could take possession within 7 days. The house was in a middle-ring suburb about 30 minutes North of the CBD and for the first time in my life, I had a permanent address in a street of houses.

I was now officially a “townie.” A derogatory term from where I’d come from, and something a rural person would never aspire to. Little did I know that this new townie, with his new partner, Lee, would be living in the same house in the same street of houses for the next forty years. In addition, as a property owner, I qualified after three months, for inclusion on the electoral roll and henceforth under Australia’s compulsory voting laws, would be fined if I failed to cast my vote in Federal and Local Body elections. Such was the flexible immigration relationship existing between our two countries in 1983.

By purchasing a modest property I’d ticked off the first of my goals, now it was time to find a way to pay the bills.

I was hopeful my NZ Rural Valuers registration certificate would have currency, but on investigation found it wouldn’t and I’d have to spend 4 years as a cadet, on the coattails of a registered Australian valuer. That wasn’t for me.

I answered an advertisement for a job with a real estate agent without luck. It appeared the skills of my previous life were of little value in the city. Perhaps I could get a truck driving job. I studied the local road code and booked an appointment at the testing centre. I fronted up with my NZ Heavy traffic license and my Farm bike license, where I sat at a computer and undertook an online exam, then a kindly old gentleman took me through an oral exam and it was time for the eye test. This potentially was a problem because as the result of a farm accident, I am permanently blind in one eye. I held the card over my right eye with my right hand and scored perfectly when reading the chart with my left eye. I then changed hands and covered my right eye with my left hand and read the chart again with my left eye. Perfect score once again. I’d passed the tests and in Australia was now licensed to drive a car, a passenger bus, a motorbike, and an 18-wheel semi-trailer.

Luckily for the citizens of Victoria, I didn’t need to fall back on a driving job and have never had occasion in Australia to drive anything larger than a four-door sedan.

A few weeks went by. I saw an advertisement one Sunday night on TV for a sales course on how to sell computers. On the TV, an earnest young man planted an acorn, and the next screen depicted him as a fully grown salesman standing beside an oak tree in an expensive suit and tie, clearly enjoying the fruits of his computer sales success. The ad was run by the Control Data Institute, a global computer company, and they were guaranteeing to find employment for all their graduates.

The cost was $12,000 for a 16-week course, a not insubstantial amount at the time. I filled in the application form, sent it off with my resume, and in due course received a phone call inviting me to sit the intelligence and aptitude tests. These were very detailed and attended by about 60 people. Twelve hopefuls including me were eventually selected but it was obvious when we met, the acceptance criteria had a lot more to do with our ability to pay the $12,000, than it did with the candidates’ intelligence and aptitude.

For me, the course proved to be an excellent investment. We were worked hard with 7 am starts and weekly assignments which necessitated studying over the weekends to meet Monday morning deadlines. Looking back, the computer studies were valuable to me as a complete rookie but focussed far too much on outdated technology. The sales subjects though were brilliant. We were psychologically tested and coached through roll plays and taught how to create rapport and listen and react to customers’ needs. When we were released into the workplace we were bristling with unjustified confidence. Sadly, the promised employment in multi-national computer companies didn’t materialise and we were placed in small microcomputer companies, most of which were scrambling to survive in an overcrowded marketplace.

As a condition of graduation, we were required to write a thesis on various topics selected by our tutors. Mine was a comparison between LINC and FOCUS, two newly emerging 4th-generation database languages. I wasn’t trained in any of this stuff of course. I’d never cut a line of code except in some practical tests during my studies at the institute, but I did the research and handed in a treatise which must have been credible because I did manage to graduate.

A day or two later the moderator of our course called me and announced excitedly that the state manager for Control Data (now Unisys) wanted to see me. We both thought I was going to be offered a sales job in this high-profile company. When I was ushered into the manager’s office, I noticed a copy of my thesis on his desk. He said, “I’m sure you know, LINC was developed by Control Data, but my sales guys are not convinced it’s as good as we are being told. Could we pay you to undertake a critical analysis with your recommendations for us please?” He wasn’t offering me a sales job; he’d assumed I had a computer science degree, and my opinion was worth paying for. That’s when I realised how shallow the computer industry was at the time. If he’d asked me to train a dog or shear some sheep, I’d have been happy to comply but when I explained my background, we were both embarrassed and the interview was over.

Around the time I was completing the course, there was a momentous event unfolding. I was driving to the institute early on September 26th, 1983, when the wing-keeled yacht Australia II edged out the American yacht Liberty II and stole the America’s Cup from the New York Yacht Club. They had never been beaten for 132 years so this win by a yacht from down under was nothing short of a miracle. As a keen follower of the America’s Cup, I was elated, and when John Raedler the commentator called out “Australia has won, history has been made, stand up Australia!” I’m embarrassed to say I pulled over to the side of St Kilda Road and waved my hands in the air beside my car to the bewilderment of other commuters who tooted and made rude signs at me as they drove past.

ORAD Computers

My first job in Australia was selling computer networks and PCs for ORAD Computers. ORAD had been supplying and supporting mechanical accounting machines for more than a decade.

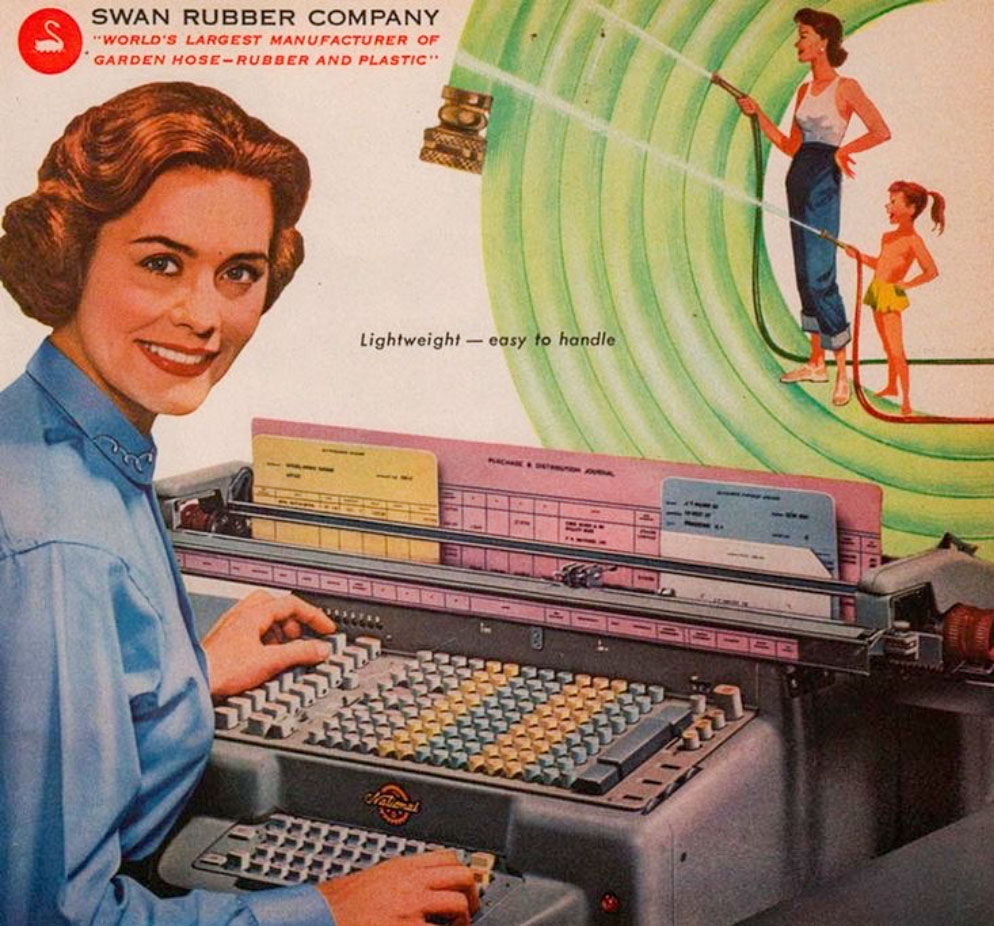

Mechanical Business Machine of the 1960s and 70s

They had a large number of clients but were under siege from microcomputer technology and were in decline. In an effort to reinvent the company the owners had appointed a new managing director, a new sales manager, and three new salespeople one of whom was me. The MD in a past life had been selling mainframes for a multi-national. He was an old fashioned, glib salesman who knew all the tricks and was the antithesis of the role model we’d been trained to aspire to. He was a big guy who after a long lunch would close his office door and, on most days, could be heard snoring gently until midafternoon.

The sales manager was capable and street smart. An interesting character who I suspected had a gambling problem. He was a good mentor though and was responsible for kindling my interest in local area networks which was to stand me in good stead in the future.

We salespeople were assigned geographical territories and were expected to cold call ORAD’s accounting machine clients, in an effort to convert them to modern technology. The customer base had been well worked over though and the pickings were slim.

The office itself was fitted out in dark colours and had no external windows. In this gloomy environment we sat at our desks under fluorescent lighting and worked the phones. An unforgiving introduction to the real world of selling with nowhere to hide at Monday morning sales meetings. Week by week my card index system evolved into a valuable list of contacts and information. I kept this locked in my briefcase in case I was escorted out at short notice due to lack of results. That day didn’t come however because the deals started to dribble in and my contact list continued to grow.

There was an upside too. I got on well with my workmates and in those days long Friday lunches were the norm. Six months passed and I’d managed to sell some large computer networks into two private hospitals and was earning good commissions but ORAD was in its death throes. The engineering support division of the business was sold off to Olivetti, The MD and sales manager were made redundant, and the less profitable sales and support arm was purchased by a company called Intelligence.

Intelligence Australia

We continued to sell Local Area Networks (LANs) but our offering was augmented by a 4GL accounting package from NZ known as CBA. This enabled us to sell total solutions and broadened our target market. I was now earning good money and thankful for the chain of events that had lured me into computer sales.

Intelligence Australia’s management style was a breath of fresh air and before long, well pleased with my income but not with my tax burden, I decided to resign. I needed to find a way to run a business of my own so explained my dilemma to David Milward the MD of Intelligence. David talked me out of moving on and in August 1984 we hammered out an agreement. I was removed from the company payroll and reverted to invoicing Intelligence for 30% of the gross profit of everything I sold. I now had a business of my own and the number of contacts in my prospecting system continued to grow.

KGM Management

A rival computer company in south Melbourne was holding a seminar showcasing their new Novel networking products. I needed to check it out but wouldn’t be welcome if they knew I was a competitor.

A rival computer company in south Melbourne was holding a seminar showcasing their new Novel networking products. I needed to check it out but wouldn’t be welcome if they knew I was a competitor.

An executive in the queue in front of me introduced himself to the seminar host as a partner from KMG Hungerford. This was a top tier accounting firm and he was enthusiastically welcomed. I was impressed!

When my turn came, I said I was a Management Consultant from KMG and received the same reception.

Several weeks later I registered a new company called KGM Management and traded successfully under that name for the next 15 years because after all, who would take the time to differentiate between KMG and KGM?

Still living in the same street of houses, 40 years on.

Next month, chapter two of A Street of Houses will be delivered to your inbox.

Ken Fife – July 2023

Well done Ken. I thought I knew a fair bit about you but learning more all the time. Willy would be proud of ypu!!

Ken and Lee–always good to hear from you. You have been on my mind lately. Really enjoyed your blog and finding your background and loved seeing your house. Pray you and Lee are well and continue to be active.Bill and I are doing well. So so hot here in Daphne AL Close to mid 90’s most of the summer. Have to be up before the sun to get your work done. I have gotten into pickleball. It is wonderful when we can play indoors. Please give our love to Lee and will look forward to your next blog… Jan and Bill Potzner

Most enjoyable reading , it’s fantastic for us to be able to look back to where we came from and to be able to document for some other people to ( maybe learn from ) if they can find time to read apart from their Phone . Well Done KEN

Hi Ken

great stuff as always….I love the job on the house!!…we had some good times there!!

Charlie

That was really interesting. Fortune always seems to shine on the hardest grafters.

Hi Alison, there were some colourful characters to contend with in the early years, during my conversion to becoming a townie but they were fun times on the whole.

Hi Alison, there were some colourful characters to contend with in the early years, during my conversion to becoming a townie but they were fun times on the whole.